Offshore wind generation faces headwinds.

The expansion of demand for wind energy is no more evident than in the European Union which is in the process of finalizing a legally binding requirement to produce 42.5% of energy from renewable sources by 2030. The current requirement is 32% but to meet the new target will require 420 gigawatts (GW) of wind energy including 103 GW offshore. This is more than double current capacity of 205 GW including an estimated 17 GW offshore.

Unfortunately, the rising cost of projects combined with supply chain delays is putting this and many other targets for wind energy at risk. So far this year, projects off the coasts of the UK, the Netherlands and Norway have been delayed or cancelled and a recent renewable energy auction in the UK failed to attract any interest at all. It is also becoming clear that the offshore industry may not have the capacity to deliver on ambitious regulated targets.

A further complication is the size of new turbines, the latest being fitted with 110 metre blades and a capacity of 12 to 15 megawatts (MW). Unfortunately, the larger units are also coming with more technical issues, largely attributable to the weight they are carrying. While these issues are proving expensive to manufacturers and insurers, they are also resulting in caution from developers in responding to new seabed license auctions. Escalating project development costs and uncertain returns on investments, in addition to fierce competition from oil and gas companies seeking to diversify, are combining to make many projects financially unattractive.

The situation is no better in the United States where there is a target to produce 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030 and 110 GW by 2050. Several developers including Orsted, Equinor, BP and Shell are being forced to cancel or renegotiate power contracts for the first commercial-scale U.S. wind farms due to start operating between 2025 and 2028. It seems clear that without subsidies, high project costs will undermine current production targets. The Business Network for Offshore Wind (BNOW) also estimates that the U.S must invest $36 billion in 110 port locations over the next decade to address the country’s offshore wind port infrastructure capacity gap.

The value of Danish energy company Orsted, the world’s largest offshore wind farm developer and which has major interests in U.S. projects, has plunged about 31% since it declared $2.3 billion in U.S. impairments in August this year. The difficulties listed were high interest rates, inadequate tax credits and supply chain delays causing some developers to walk away from contracts rather than absorb major financial losses.

A recent letter to President Biden from the Governors of Maryland, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York and Rhode Island asked for leniency in qualifying offshore wind projects for new clean energy tax credits, speedier permitting, and the establishment of a program to direct a portion of the revenue generated by federal offshore wind leases to states.

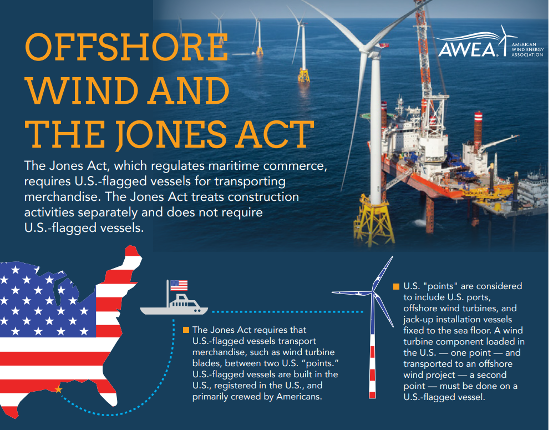

A further complexity in the United States is the application of the Jones Act to the offshore wind energy industry. In 2021 The Washington Post ran a story describing the example of two wind turbines constructed off the coast of Virginia Beach. Because the vessel used for the installation of the turbines was not Jones Act-compliant since no such vessels that meet the Jones Act currently exist, the vessel was forced to operate out of Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The first Jones Act compliant vessel, to be named Charybdis, is not expected to be available until 2024 and even then, at the extremely high cost of $500 million, about double the cost of building a similar vessel in an overseas yard. Charybdis is being built at the Keppel AmFELS shipyard in Brownsville, Texas but many industry experts are suggesting that a relaxation of the Jones Act will be required if the U.S. offshore energy market is ever to be viable.

For now, the U.S. is facing the choice of using feeder barges to ferry feeder components to an on-site foreign flagged installation vessel or paying eye watering sums of money to construct a Jones Act‐compliant installation vessel which is a long and uncertain process given the vessel’s complexity and the lack of available shipyards.

featured Image Courtesy offshorewind.biz