Growing Impatience with Container Losses at Sea

The incident in May this year, when the Singapore registered container ship APL England lost some 40 containers overboard off the coast of New South Wales, highlighted not only a continuing problem in the reliability of lashings but also the growing impatience of Port State Authorities with the consequences. In the case of APL England, the vessel was in transit from China to Melbourne and about 73 kms S.E. of Sydney when an engine failure left the vessel to the mercy of the elements resulting in unusually heavy rolling. In addition to the loss of containers, 74 were judged to be damaged including six hanging overboard. Rather than continue to Melbourne the vessel returned north to the port of Brisbane as a port of refuge. The vessel had previously lost 37 containers in the Great Australian Bight in August 2016, due to heavy rolling in rough seas.

Reflecting a growing trend, the Australian Maritime Safety Agency (AMSA) issued a direction ordering the vessel owners to search for and recover the missing containers using drift modelling and analysis of container sightings following the incident. The strict approach taken by AMSA on this occasion was likely influenced by an incident in June 2018 when the Yang Ming owned YM Efficiency lost 81 containers overboard off the coast of Newcastle resulting in large volumes of debris being washed ashore on local beaches. Facing intense criticism, AMSA pointed out at the time that while Yang Ming had been quick to clean up what washed ashore, it had not addressed the recovery of missing containers and sub-surface debris.

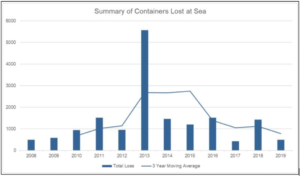

While the impact of a loss of containers can be devastating for everyone involved, The World Shipping Council (WSC) representing container lines has released its findings following a recent survey of its members on what current trends are. The WSC undertook the first survey of its member companies in 2011, with updates published in 2014, 2017 and 2020. A review of the results of the period 2008-2019 concluded that there were on average a total of 1,382 containers lost at sea each year. Also, for context if not ease of mind, more than half of all containers lost at sea can be attributed to major events including the total losses of the MOL Comfort (4,293 containers) in the Indian Ocean, MV Rena (900 containers) off Tauranga NZ and SS El Faro (517 containers) when sadly taken by Hurricane Joaquin in the Caribbean. For the 3-year period ending in 2019, the average number of containers lost annually actually fell to 779.

WSC goes on to point out that the number of containers lost overboard represents less than one-thousandth of 1% of the roughly 226 million containers carrying $4 trillion worth of cargo moved by ships in 2019. “The industry is encouraged by the declining trend line indicated in the latest report and continues to work on solutions that will bring the number of containers lost at sea each year to as close to zero as possible,” said John Butler, WSC President and CEO. “The industry is also pursuing a number of initiatives to improve container safety and further reduce the number of containers lost.”

Graph courtesy World Shipping Council

Despite the encouraging numbers, container lines are keenly aware that the loss of any one container is one too many and that as ships get bigger, the challenge of providing a 100% effective lashing system will also grow. A number of initiatives have therefore been launched such as the award of the DNV GL RSCS+ Class Notation. The class society describes this as the world’s first full three-dimensional calculation method that reveals new options for container stowage optimization using StowLash3D software which also provides enhanced Route Specific Container Stowage.

This latter point may prove to be an interesting development given that the Dutch Safety Board recently completed its investigation into the loss of containers from MSC Zoe off the Wadden Islands in January 2019. The islands form an archipelago at the eastern edge of the North Sea stretching from the northwest of the Netherlands through Germany to the west of Denmark. MSC Zoe lost 345 containers while on a coastal passage to Bremerhaven. The loss was initially attributed to the vessel’s high stability but the Dutch Safety Board engaged the Deltares research institute and the Maritime Research Institute Netherlands (MARIN) to further investigate.

Using scale modelling and ship’s recorded data, Deltares concluded that the water depth on the night in question was between 21 and 26 meters. There was a northwesterly storm with winds up to Beaufort 8 on the port beam with a wave height of up to 11 metres resulting in wave crests impacting the port side with considerable force. That said, MARIN concluded that four factors in combination likely led to the loss of containers:

1. Stability

Ultra Large Container Vessels (ULCS) container ships such as the LOA 395m and beam 60m MSC Zoe are inherently stable and when a force is applied to them they generally return to a position of upright equilibrium position quickly. This results in a short natural period of roll of between 15 and 20 seconds which is close to the wave periods that occur above the Wadden Islands during a northwesterly storm. As a result, roll resonance can occur, causing angles of heel of up to 16 degrees and under such conditions large container ships can roll quite steeply with large accelerations generating forces that can exceed safe design values.

2. Draft

In the conditions experienced by MSC Zoe, in addition to rolling, the ship can pitch heavily with the risk at a deep draft of touching the seabed. In an extreme case this can result in shocks and vibrations, the impact of which can cause container lashings to fail.

3. Water on deck

This impact of green water under, over and against containers can ultimately result in stack failure.

4. Vibration

The conditions experienced by MSC Zoe are estimated to occur only once or twice a year in that location, however, MARIN concluded that the loss of containers from smaller vessels in the area begs for more research to be conducted. The investigation also concluded that both the northern and southern shipping routes near the Wadden Islands are subject to comparable route-specific risks for large container ships hence the potential to tie into the DNV GL Route Specific Container Stowage approach.

The Dutch Safety Board also participated in a joint investigation with Panama as the relevant flag state and with Germany. The investigation produced five main recommendations for further review:

- The design requirements for lashing systems and containers,

- The requirements for loading and stability of container ships

- Obligations with regard to instruments providing insight into roll motions and acceleration

- Technical possibilities for detecting container loss

- Adjustments to North Sea shipping routes for IMO consideration

An interesting conversation to follow – watch this space.