The Race for Long Term Lng Supply Contracts

As the world has already learned, Russia’s war on Ukraine has abruptly turned the energy supply map on its head. The supply lines of coal, oil and gas have fundamentally shifted away from dependency by western nations on Russia as a primary supplier and the logistics of managing this change have almost overnight provided the marine industry with unforeseen challenges and opportunities.

Being heavily dependent on Russia’s Gazprom for oil and gas, the example of Germany’s abrupt change of direction is a compelling case study. The country has chartered five floating LNG storage and regasification units (FRSU) and last month inaugurated its first floating LNG terminal in Wilhelmshaven after 194 days of breakneck speed construction of the supporting infrastructure. This was only possible thanks to the elimination of environmental impact assessments and permitting bureaucracy. The first chartered Høegh LNG unit, Høegh Esperanza, has already taken up position to begin receiving LNG imports from Australia and the United States. The terminal will have an eventual capacity of up to 7.5 billion cbm which is a good start in replacing the 50 billion cbm supplied annually by Gazprom. By the end of 2023, the plan is to replace up to 60% of Russian supply.

Planned Floating LNG (FLNG) terminals in Germany:

|

Location |

State/Private |

Projected start date |

|

Wilhelmshaven |

State |

Winter 2022/23 |

|

Wilhelmshaven |

State |

Q4 2023 |

|

Brunsbuttel |

State |

Winter 2022/23 |

|

Stade |

State |

Q4 2023 |

|

Lubmin |

State |

Q4 2023 |

|

Lubmin |

Private |

Q4 2022 |

| Rostock | Private |

To be confirmed |

Also on the supply side, following extended negotiations, Germany has signed 15-year contract with Qatar Energy effective 2026 through the American energy multinational ConocoPhillips, which will execute the LNG exports to Germany. Australia has meanwhile already diverted a shipment of 75,000 tonnes of LNG to Germany via Rotterdam.

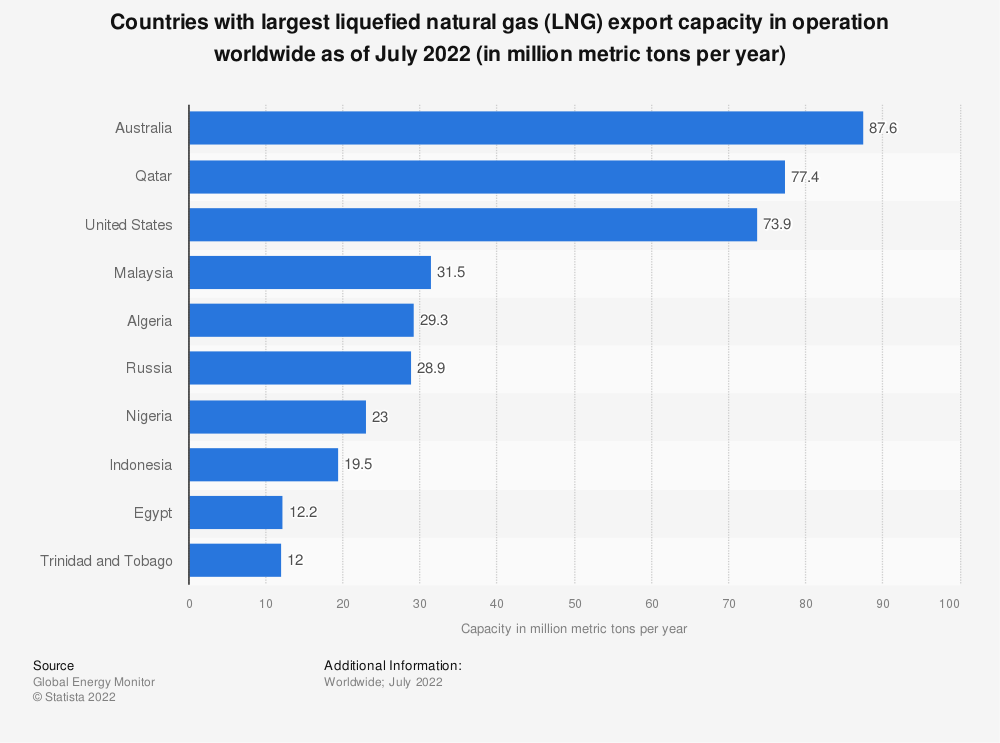

The ramping up of LNG production across the globe over the last 10 years has proven to be timely. The United States has switched from being a net LNG importer to being the world’s largest supplier in 2022, enabled in part to the opening of the Panama Canal expansion in 2015. Exporting through eight terminals, primarily in the Gulf of Mexico, (with more under construction or planned) the country now meets around 20% of global demand with exports of 11.5 billion cbm/day against world demand of around 53 billion cbm/day. For its part, Australia is set to export around 80 million tonnes in 2022 from 10 export terminals, primarily situated in Western Australia. Production has traditionally been exclusively to Asia but with the new European demand, this is certain to diversify.

Until recently the world’s top exporter of LNG, Qatar is also not sitting idle. Capacity expansion from the current 77 million tonnes to 126 million tonnes is expected by 2027. The country is unique in that much of its supply is carried in Qatar Energy owned LNG carriers including some of the largest in the world. The country has also recently signed a 27 year supply contract with China’s Sinopec, that country being the world’s largest importer of LNG and growing.

From a shipping perspective, this is all good news for owners of LNG carriers since the tonne/miles being steamed has created significant pressure on charter costs which this year have exceeded US$ 400,000/day at times both in the Pacific and Atlantic basins for a standard 174,000 cbm LNG carrier.

Sadly, Canada is missing the boat. Of 20 LNG export projects having been pursued over the past 10-15 years only one significant project has made it through the red tape of regulatory and environmental hurdles along with all manner of community and indigenous opposition. The successful project is the Shell lead LNG Canada which is currently under construction in Kitimat on the north coast of British Columbia.

Comprising two LNG trains in the first phase, the terminal will have the capacity to export 14 million tonnes a year of LNG over its estimated project life of up to 40 years. It is estimated to cost C$40bn ($31.2bn), making it the biggest energy investment in Canada till date. The project is a joint venture between Shell Canada Energy, a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell (40%), North Montney LNG (25%), Phoenix Energy (15%), Diamond LNG Canada (15%), and Kogas Canada LNG (5%). The project will be supplied by a 670 km gas pipeline currently 80% completed despite considerable cost and logistical challenges. First exports from LNG Canada are projected for 2025.

Smaller projects, include the US5.1 billion Woodfibre LNG project in which Enbridge has recently secured a 30% stake from proponents Pacific Energy. The project capacity is 2.1 million tonnes/year. Another project going through the feasibility regulatory process is Cedar LNG which is a First Nations lead project, also in Kitimat.

As a consequence of the changing LNG dynamics, orders for large new LNG carriers at around 170,000 cbm, US$240 million per vessel, are going through the roof. Orders with shipyards in China and South Korea for around 120 large (in excess of 140,000 cbm capacity) LNG carriers have been placed this year alone bringing the global order book up to around 280 vessels. South Korean shipbuilders have contracted for more than 85 LNG carriers this year representing 75% global orders with Chinese shipbuilders contracting the balance.

Russia has placed considerable political and financial capital into its own LNG exports but the geopolitical struggle now underway seems set to undermine any meaningful success. As often happens, when the world economy goes sideways at short notice, shipping is on hand to pick up the pieces.

Feature Image Courtesy Høegh LNG