Shipyards in Crisis

The scrapping of a number of older cruise ships has been much in the maritime media since the onset of the global pandemic effectively shuttered the cruise industry. However, a headline that caught my eye a couple of weeks ago was that it is 500 days since the last Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC) was sold to a scrapyard. There are a number of reasons for this, primarily that until very recently VLCCs have been making strong returns, but also the uncertainty generated by IMO emission reduction targets. Just to remind you these are to reduce total emissions from shipping by 50% in 2050, and to reduce the average carbon intensity by 40% in 2030 and 70% in 2050, compared to 2008.

The challenge that these targets represent for shipowners is very real in so much as the technical road map to compliance is as yet unclear thereby making investment in new ships which may ultimately be unable to meet yet to be regulated emission reduction milestones a significant economic risk. This dilemma for shipowners coupled with global economic uncertainty translates to a major problem for shipyards, hence a global order book for new vessels sitting at 7% of the existing fleet, the lowest for 30 years.

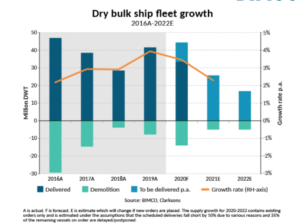

The single largest sector of shipping is that of bulk carriers ranging from Very Large Ore Carriers (VLOC) in the 400,000 tonnes deadweight (DWT) range to Handysize vessels in 35,000 tonnes DWT range. This sector has seen both deliveries and demolitions rise over the course of the pandemic but contracting has now fallen steeply. Thus far in 2020, we have seen net growth of around 2.8% (40 million tonnes DWT) in the dry bulk fleet which in capacity terms now exceeds 900 million tonnes DWT, a new record. The growth in new tonnage deliveries has fortunately been offset by an increase of around 70% (9 million tonnes DWT in scrapping compared to 2019.

At the same time, we have seen the order book for new dry bulk vessels fall to around 108 vessels of 63 million tonnes DWT, a 59% decline representing the lowest order book in this sector in 16 years. The majority of orders are for Handymaxes (between 60 and 65, 000 tonnes DWT) of which around 60 have been ordered to date.

By comparison, container shipping capacity has expanded by around 2% this year to just over 23 million TEU which represents a four-year low in net growth. The sector had a torrid first half of the year thanks in part to the pandemic and was forced to carefully manage capacity in the main trade lanes. It is predicted that as much as 300,000 TEU of capacity in the form of older, heavy fuel consuming container ships could go for demolition this year. While there are a few headline-grabbing announcements such as that from COSCO owned OOCL in the past week that they have ordered 7 new 23,000 TEU capacity vessels in China, the order book for container vessels is at its lowest since 2003.

It is perhaps worth noting that after peaking in 2009 when orders for new ships represented 52% of the global fleet. It has taken a decade for the industry to recover from the frenzy of over-ordering in response to the economic boom of 2005-08 when ships were attracting unsustainable freight levels.

Looking ahead, it seems that the lack of orders will force further restructuring and shrinkage in ship building capacity. There was some good news for South Korean yards this past summer when $20 billion in contracts to build approximately 100 LNG carriers for Qatar Petroleum was signed with Hyundai Heavy Industries, Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering and Samsung Heavy Industries, thereby keeping them busy through to 2027. These mega yards will for sure continue to slug it out with Chinese yards for every order with China having already acknowledged a 12% decline ib orders this year. The mid-sized South Korean yards of Hanjin Heavy Industries & Construction, STX Offshore & Shipbuilding, and Dae Sun Shipbuilding and Engineering are each reported to be up for sale despite traditional generous government support to the industry.

The situation is no less uncertain for European yards specializing in the cruise, ferry and offshore sectors. Given the debt burden of the cruise lines suffering from almost zero revenue this year, it is hard to envisage any short or even medium-term return to placing new orders. They do however seem intent on maintaining current orders but various levels of state intervention have been required to keep the yards afloat.

It remains to be seen how far global shipyards are prepared to slash prices for new vessels in an effort to entice reluctant ship owners to place orders. The vicious circle of price slashing leading to over capacity and low freight rates has been hard to break this time round but the political pressure to maintain strategic industries such as shipbuilding should probably not be under-estimated.