The China Factor in Shipping

A study released a few days ago by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), concludes that commodity exports to China are likely to fall substantially as a consequence of Covid-19. According to the report, in a worst case scenario China’s 2020 demand for commodities could fall by as much as 50% compared to 2019. With China absorbing around 20% of global commodities, this would inevitably have a severe impact on the world’s ports and commodity export dependent economies, further compounded by the continuing trade war with the U.S. Perhaps understandably, China has decided to temporarily drop the publication of annual growth targets.

The international container industry has responded to the 2020 world economic slow down by slashing sailings across the globe in an effort to balance supply with demand in an effort to shore up freight rates. As many large international retailers fight for survival there is only minimal pressure on supply chain delivery dates and in many cases “the later the better” to preserve cash flow. This when combined with a dramatic fall in oil (bunker) prices has led some container carriers to further reduce speed and even to sail the longer route between Asia and Europe via the Cape of Good Hope as an alternative to the cost of a Suez Canal transit. This has shaken the Suez Canal Authority which has responded by slashing rates by 17% for vessels trading to and from Europe and by up to 75% for vessels trading to and from the U.S. East Coast. All very well, but where does all this leave the shipping industry which has invested so much capital in shared optimism for continued Chinese economic growth?

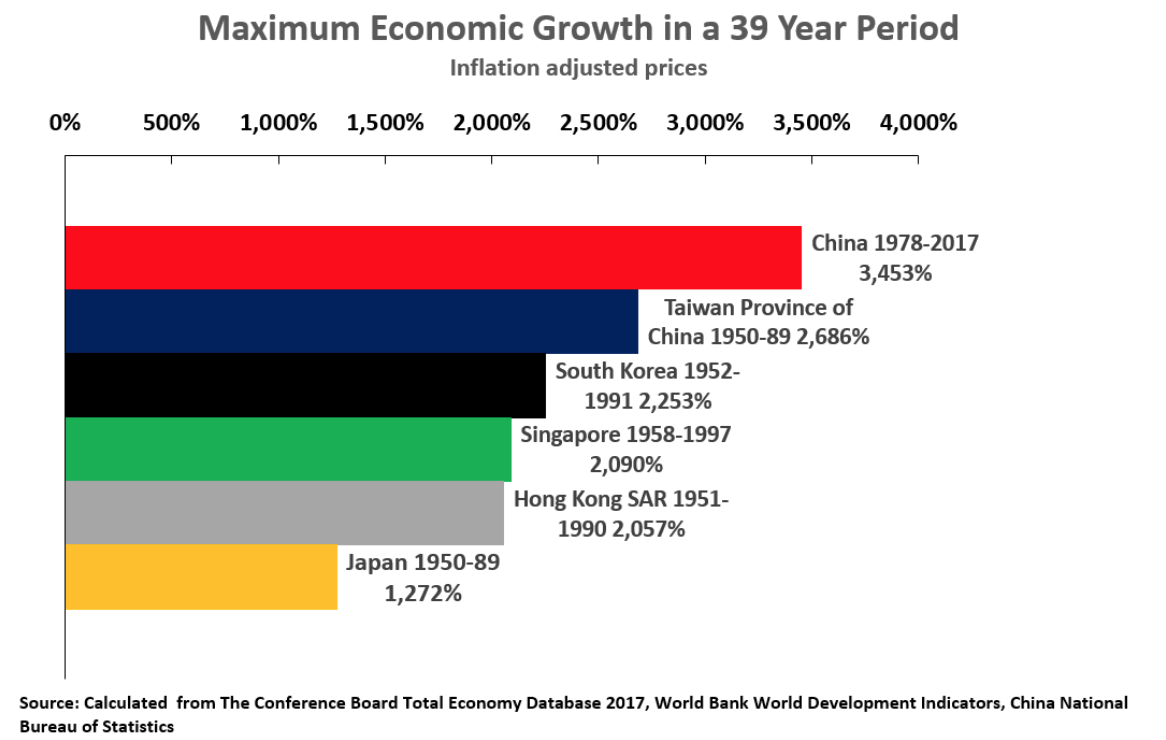

The answers are complex but it must be appreciated that short term bumps in the road such as trade sanctions and Covid-19 are without consequence to China’s long term objective of maritime trade domination. I say this, not as a casual observer but as someone who managed a joint venture marine terminal in China in the early 1990’s and witnessed first-hand the seeds being sown in pursuit of the task. The “open-door policy” to foreign businesses announced by Deng Xiaoping in 1978 was implemented hand in glove with infrastructure development, the likes of which the world has never seen. The pace of construction of entire new cities, ports, airports, the world’s largest high-speed rail network and a comprehensive new road network has been staggering as has the emergence of a middle class comprising hundreds of millions of new consumers. The global marine industry has thus been a major beneficiary on the demand for raw and finished materials along with the country’s emergence as both a manufacturer and consumer, including the world’s largest car market, all from an almost standing start in only 30 years. A breathtaking achievement by any standards.

Turning specifically to maritime dominance, China has made a number of strategic moves, examples of which are:

1. Ports

As noted above, the country has invested heavily in port infrastructure, many ports being unrecognizable from their pre turn of the century selves. Take for example Shanghai which has leapfrogged the competition to become the world’s no.1 container handling port with a throughput of 43 million TEU in 2019. Overall, China is far and away the world’s largest container cargo handler – processing around 30% of global traffic or around 715,000 containers a day and hosts 7 of the world’s top 10 container ports including Hong Kong. A number of terminals operate as joint ventures with overseas-based port operators or shipping lines with all the attached benefits of imported technology.

2. China COSCO Shipping

The development of China Ocean Shipping Co. (COSCO) from its foundation in 1961 as a modest operator of often old second-hand tonnage to its current status as the world’s 3rd largest container line has been remarkable. This follows the merger with compatriot shipping line China Shipping in 2016 and the $6.3 billion purchase of Hong Kong’s Orient Overseas Container Line (OOCL) in 2017.

China COSCO Shipping today operates a fleet of more than 1000 ships in most sectors of shipping including containers, all classes of bulk carriers and tankers, ro-ro vessels, heavy lift carriers, LPG and LNG carriers. The company is also in the process of building a domestically-built fleet of open hatch bulk carriers for the carriage of wood pulp, thereby competing head-on with the Norwegian based carriers which traditionally dominate in this market.

Profile of new COSCO pulp carriers and right Greek PM Kyriakos Mitsotakis with President Xi JinPing.

COSCO Shipping Ports Division is a further strategic arm of the company with investments across the globe including in South Korea, the United States, Peru and Greece. Despite dockworker opposition, the company took full advantage of the financial crisis in Greece by taking a 51% stake in the port of Piraeus in 2016 for $312 million as a condition of the Greek government’s receiving a further bale out from the European Union. During a visit to the port in November 2019, Chinese President Xi JinPing further announced plans to turn Piraeus port into the biggest commercial harbor in Europe, spending about 600 million euros ($660 million) to boost operations, including investments of 300 million euros by 2022 which once concluded will allow it to acquire an additional 16% stake in the port.

3. Shipbuilding

From humble low-tech construction of vessels for the domestic fleet, China’s shipbuilding industry has emerged as a world leader of strategic national importance with almost unlimited government support. For the last 5 years, Chinese yards have enjoyed around 40% of world shipbuilding both in terms of the number of orders and deadweight tonnage. More than 90% of orders were for export thereby providing valuable financial returns, securing hundred of thousands of jobs and access to designs and technology. Coupled to shipbuilding is generous finance terms provided by Chinese banks.

In this context, the Greek connection should not be overlooked as the country’s merchant fleet remains the world’s largest by some margin and has undoubtedly benefited from the close relationship between the two countries.

4. Cargo preference policies

Largely unwritten rules provide a wide range of cargo preference by the Chinese state to Chinese ship owners and charterers. China is the world’s largest oil and natural gas importer and today accounts for some 25% of global energy consumption. Maritime resources provide an ever-extending global reach that has the procurement of energy supplies at its core, namely oil and gas in any area, any country at any time with oil and gas constitute a rising 30% of China’s total energy demand. Even as China leads the world in investment in renewable energy and much of the world debates the end of oil and gas, China knows full well that these energy sources will remain indispensable for decades to come.

Indeed, when global oil prices recently plummeted in response to a collapse in demand as the world went into Covid-19 lockdown, guess who was buying – China of course. On May 18, brokers estimated that China had 117 VLCCs alone inbound to the country’s oil handling ports, the country having spot fixed cargoes in April when prices were rock bottom in Russia, Alaska, Canada, and Brazil.

5. Commodity price control

When a single country is purchasing such a large percentage of the world’s resources, that country inevitably gains a degree of control over market prices. Whether that commodity is iron ore, coal, grains, wood pulp or logs, it doesn’t matter, the principle remains the same i.e. build up strategic stock levels and then halt buying for a while until prices collapse. The examples of this are too many to mention and of course the impact on the bulk shipping industry in particular is devastating. The Baltic Dry Index could to some extent be renamed the China Dry Index.

6. Control

This is perhaps best illustrated by providing an example. To counter Chinese influence on freight rates, the Brazilian multinational Vale S.A. elected to build its own fleet of Very Large Ore Carriers (VLOC) to move cargoes of around 400,000 tons of iron ore from Brazil to China. The first vessel sailed in 2011 but was banned from discharging in Chinese ports under pressure from a collective of Chinese shipowners who under the guise of “port safety” objected to their effective exclusion from the trade. Vale tried work arounds including establishing an expensive transhipment operation in Malaysia but Beijing’s ban on the vessels was effectively lifted only after a transfer of vessel ownership to Chinese interests, including COSCO, which then signed a 25year freight contract with Vale. Vale also entered a contract with China Merchants Group to build 10 more VLOCs and charter them back over 25 years. Thus the “port safety” issue was quietly and efficiently resolved.

former Vale owned VLOC now under Chinese ownership

In conclusion, it is perhaps understandable that an economy that is set to be the world’s largest by 2030 seeks to have the reassurance of a large merchant fleet in support of its national interests. However, this aspect of long-term strategic planning, despite its importance, is not well understood in the west. Sadly, such issues are to be found on the “too difficult shelf” or sometimes simply lost in the debate over trade policies.