China’s Arctic Silk Road

When it comes to discussions of the Arctic here in Canada, there is an emphasis on the importance of maintaining sovereignty and preservation of the unique environment but with far less consideration to the economic opportunities that the Arctic represents. By contrast, Russia and China are both aggressively moving to advance their Arctic interests, even though China is not geographically speaking an Arctic power.

In 2013, the Arctic Council comprising Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States voted to accept applications for observer status from China, Japan, South Korea, India, Singapore and Italy. In effect, observer status recognises that a non-Arctic country’s interests are significant enough to allow it to sit in on meetings but does not extend to the right to introduce new projects or raise issues of concern to the council, unless invited to do so by the Chair. Other countries having been previously granted observer status are France, Germany, The Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. So why the high level of Chinese interest?

The Arctic holds an estimated 13% (90 billion barrels of oil) of the world’s undiscovered conventional oil resources and 30% of its undiscovered conventional natural gas resources (47 trillion cubic meters) according to an assessment conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The value is estimated at a staggering $35 trillion. However, how much of these resources is commercially viable remains a question mark on account of environmental sensitivity and disputed sovereignty claims between the players, the area north of the Arctic Circle being divided between Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States. Internationally recognized exclusive rights to seabed resources, the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) under rules established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), extend up to 200 miles beyond a country’s coastline. Beyond this, the natural prolongation of the continental shelf drives many extended seabed boundary claims.

Yamal LNG

Predictably, non-Arctic nations seek to exploit its resources through companies that have operations in the Arctic, and through joint ventures with Arctic countries. From a shipping perspective, we have seen the development of such projects as Yamal LNG (China, Russia & France) which is supported by a fleet of 15 ice-strengthened LNG carriers in conjunction with the opening of both the Northern Route and the NW Passage which provides alternative access routes to the consumers of Europe and Asia. Russia also has a formidable icebreaking capacity. President Putin has stated that by 2035 Russia’s Arctic fleet will operate at least 13 heavy-duty icebreakers, nine of which will be nuclear powered.

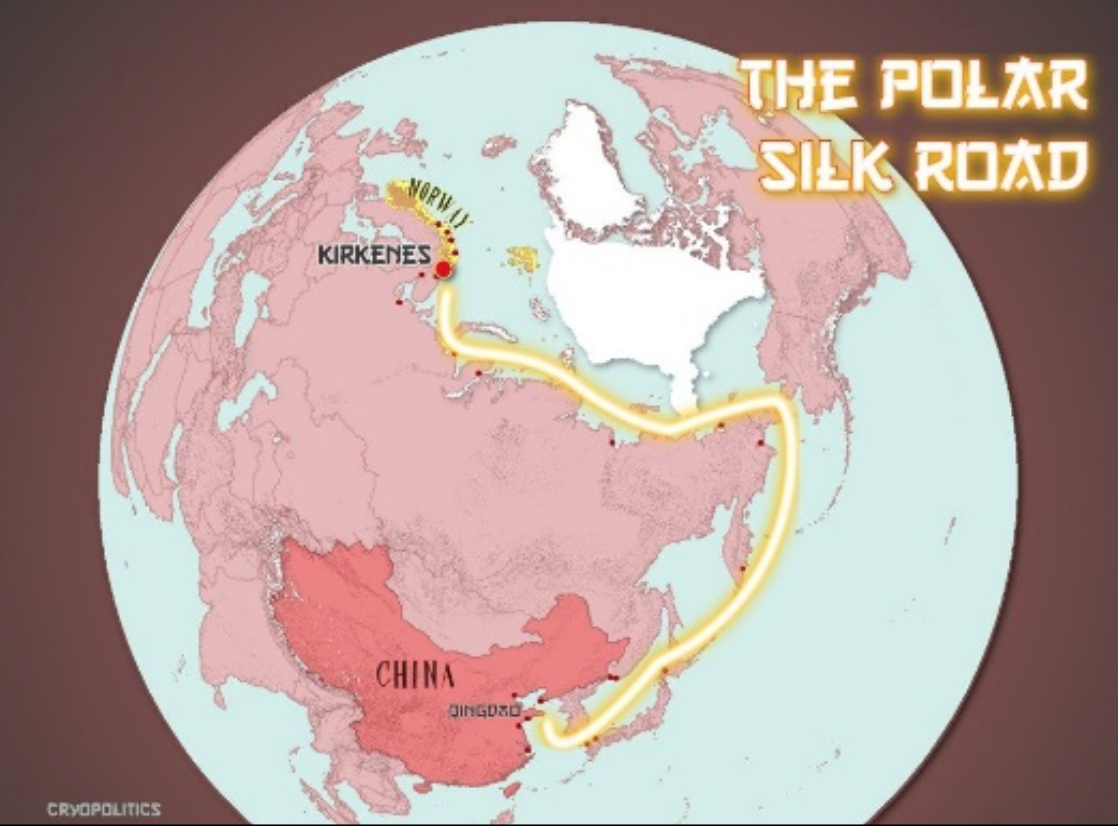

So, what is driving China’s interest? By 2030 the Arctic may well be free of sea ice during the summer months thereby further offering alternative routeing for shipping, an opportunity China is currently moving to exploit with a series of development projects. By leveraging it’s financial, technical and scientific research capacity with Russia, China envisions an Arctic Silk Road as an extension of the already flourishing Belt and Road initiative in order to take a share in the Arctic’s untapped wealth. Russia controls more than half of the Arctic along its border and only recently, China, signed an agreement with Russia’s Rosneft to drill in the Barents Sea. The impacts of western sanctions on Russia is certain to see an expansion of these arrangements.

The concept of an “Arctic Silk Road” was initially proposed in 2017 with China also expressing “protection and development of the environment with current and long-term interests balanced, and sustainable development promoted.”

In addition to the Yamal LNG project, China is participating in:

- Development of the Payakha Oilfield on Russia’s Taymyr Peninsula

- Expansion of the Russian ice-free port of Zarubino to the southwest of Vladivostok and close to the Chinese border

- Development of the new Arkhangelsk deep-water port, the largest city on Russia’s northern coast, situated close to Finland.

- Establishment of the China–Finland Arctic Monitoring and Research Centre

- Establishment of the China–Iceland Arctic Science Observatory in the city of Karholl in northern Iceland.

In support of its Arctic interests, China is also developing access capability in the form of ice breakers. In 2019 the country commissioned the 122m long Xuelong 2 (Snow Dragon 2), the first domestically designed and constructed ice breaker. Its predecessor was the Xuelong was a converted 1993 built Ukranian cargo vessel.

Xuelong 2

There seems little doubt that China will eventually follow the lead of Russia in the development of a nuclear ice breaker program. Indeed, there were reports in 2019 that just such a program has been launched, thereby leaving Canada and the United States to play catch up, both countries currently being reliant on a single heavy Arctic ice breaker, in Canada the 1969-built Louis S. St. Laurent and in the U.S. the 1976-built Polar Star. That said, in February 2019, the U.S. Congress allocated $675m for the design and construction of the first in class of a program for 3 new heavy ice breakers. Unfortunately, the Canadian plan to build a new Polar ice breaker has fallen foul of significant delays in the implementation of the National Shipbuilding Strategy and rather than build the vessel in Vancouver as originally intended, she now seems likely to be built in Quebec at a cost well exceeding C$1 billion by latest estimates.

The history of the Arctic has been written by curious explorers and visionaries who appreciate its importance and its potential. As a new chapter is written, let us spare a thought for those who brave the region’s challenging environment in protectively unleashing that potential.